Our Mummy

When she arrived in St. Petersburg in 1925, the mummified Egyptian woman who now rests with the Museum of History did so without a name. What remained of her wrappings did not include any writing, and the coffin she arrived with was bare—on top of that, the beard it sports suggests it might not have even belonged to her to begin with.

Over the years, the Museum has had her examined, x-rayed, and CT scanned to better understand how she lived, how she died, and how she was prepared for the afterlife.

The word mummy declares her as an object, but she is much more than that. She is a woman who, at the very end of her life, was mummified. That was the custom of the culture she lived and died in. It is a custom which has allowed us to shed some light on the way she might have lived nearly 3,000 years ago.

Her Life

While she was already unwrapped and separated from her original coffin, and no records arrived with her, there is still much we can tell about her life.

She was, for instance, mummified in the style of the Second Intermediate Period, or the New Kingdom, from around 1630 to 1075 BCE. The fact that she was mummified at all sheds some light on her social standing; only the upper or middle classes could afford such a luxury.

She was young—a dentist suggested she was around 30 to 35 after looking at her teeth in 1940, but a radiologist looking at her x-rays in the 1970s surmised she was younger, closer to 26. There is no obvious cause of death that can be seen from her bones, but calcification in her chest was found in a 1988 CT scan which suggests she had tuberculosis.

In general, women in ancient Egypt were considered legally equal to men. They could own property, divorce their husbands easily, and even left their own wills. However, ma’at, or the sense of cosmic balance that governed every aspect of Egyptian life, dictated that women’s role in society was often centered around the home, while men were responsible for more external things, like the government if they were royal, or the management of the farm, if they were of a lower class. Even then, women often held professions such as brewer, doctor, musician, artisan, priestess, or scribe.

In the New Kingdom, noble women are often shown wearing sheer linen dresses, cinched at the waist with a sash or belt, and sometimes covered with a capelet. Collar-style necklaces were common, as well as headpieces. Wigs were also fashionable during this time, sometimes to cover shaved heads. Our mummy still has short, red hair, though the color may be a result of the mummification process.

All genders wore kohl around their eyes—the black eyeliner which is famous to the Egyptians—to protect themselves from the glare of the sun, a practice which is still used in that area today. Cosmetics in general were used by everyone, most notably perfume. Kyphi, the most common kind, could be applied like modern perfume, by wafting it into the air and walking through the cloud.

These features of fashion and daily life could have all been relevant to the life of the mummified woman who now rests in the Museum of History.

Her Afterlife

In 1922, for the first time in thousands of years, our unknown ancient Egyptian woman appears in the written record. The St. Petersburg Times reports that George Roberts, one of the owners of Avery & Roberts Marine Ways, has come into possession of a mummy.

Perhaps a fan of a good story, Roberts gave a couple of different answers when he was asked where she came from. In one article, he claimed he received her from a friend who worked in the Valley of the Kings, and in others, she was used as a form of payment by a ship in need of repairs.

It is this second story that has a kernel of truth.

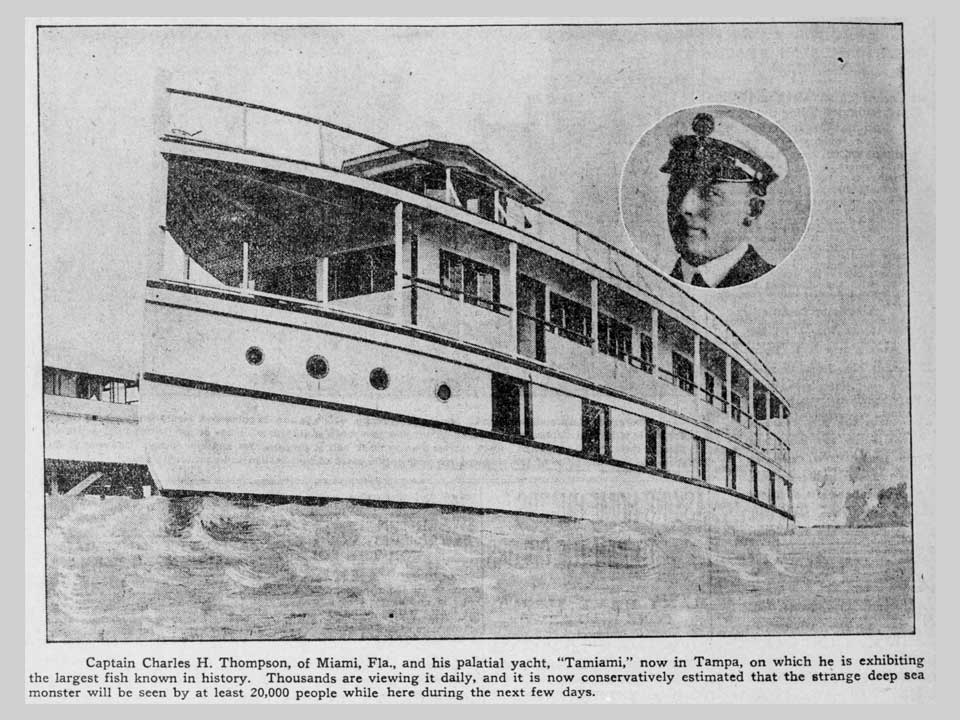

In reality, she had been left with Avery & Roberts Marine Ways by a ship named the Tamiami for reasons unknown. For many years, the story of her arrival in St. Petersburg has centered on this ship, which has long been remembered as a circus boat. This description, however, is not entirely accurate.

The Tamiami was a floating museum. From 1918 until about 1927, the yacht traveled up and down the Mississippi River and its tributaries, then up the east coast, as far north as New York. It would stop at cities along the way and open for visitors for days or weeks at a time.

Unlike a circus sideshow, it had a singular focus on marine wildlife. Even its oddities were from the ocean. Over the years, the ship held two live manatees, live alligators, and, of course, its headlining exhibit: the taxidermied body of a whale shark, the first ever seen or caught by humans.

An Egyptian mummy doesn’t really fit in with the other exhibits. They never advertised that they had one on board, except for one singular time in Pensacola, three days before the Tamiami showed up in St. Petersburg. In an article for the Pensacola News Journal, the lid of her coffin had to be removed before they could see her, which could mean she wasn’t even on display to begin with.

It’s possible that she was brought aboard the Tamiami in Pensacola, explaining why that is the only article in which she appears. Or, perhaps, they had her from the beginning, and never felt the need to mention it. It is impossible to know, and there are no relevant mentions of mummies in the cities where the Tamiami stopped.

From Pensacola, the Tamiami stopped in Clearwater before heading to St. Pete. On May 4, 1922, it docked with Avery & Roberts Marine Ways—yes, for repairs. Right after it left, George Roberts was in the paper, talking about having a mummy at the Marine Ways.

George exhibited her himself for a year or so. Journalists and other interested individuals could come by and see her. In 1923, he even mentions putting together an exhibit on Central Avenue. Whether or not this actually happened is unknown, but after Lord Carnarvon fell victim to “King Tut’s Curse”, Roberts admitted to hiding the mummy from a superstitious public.

Within two years, however, the mummy had a new home: the St. Petersburg Memorial-Historical Society Museum. Donated by Bayboro Marine Ways (the fresh new name for Avery & Roberts) in May of 1925, she has remained here ever since.